Figure 15.1-1 - The first lead of Double Oxford Minor

Figure 15.1-1 - The first lead of Double Oxford Minor| Home page | Bellringing | Talks & lectures | Fell walking | Settle - Carlisle | Metal sculpture | Brickwork | Journeys | Ergonomics | The rest | Site map |

Last updated on: 04-October-2024

The glossary in The Tower Handbook included diagrams to explain terms that were best defined visually. These are reproduced below together with their accompanying text, using the original Figure numbers: 15.1-1, etc. (Section 15 was the glossary.)

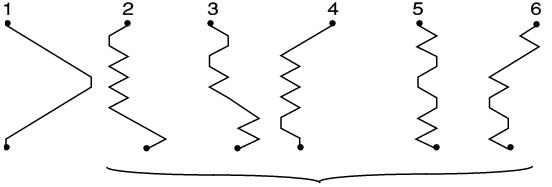

The diagram shows a lead (the basic repeating block) of a treble dominated method . In most methods (but not for example Grandsire) rounds is the row immediately following a point of symmetry (the lead end change ). The bars show where the places are made in each change , and this is reflected in the place notation on the left.

Figure 15.1-1 - The first lead of Double Oxford Minor

Figure 15.1-1 - The first lead of Double Oxford MinorThe full place notation is X 14 X 12 X 36 X 56 X 36 X 36 X 14 X 12, but this is normally abbreviated to X14X12X36X56 le 12, or X4X2X3X5 le 12. See section 13.10.q.

Drawing a line through the path of each bell will give these patterns.

Drawing a line through the path of each bell will give these patterns.

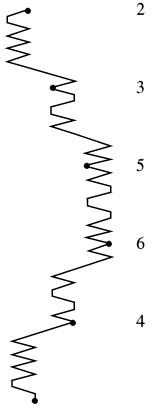

The treble returns to lead and so repeats a hunting path. The other bells move to a different position at the next lead head, so they then do the work starting at the new position. This process continues until they have done the work of all the other working bells, in the order of the work. Drawing these end to end gives the 'blue line' of the method

The complete blue line for Double Oxford Minor is shown on the right. The dots show the start points for each inside bell. It is shown in the conventional way running from top to bottom. This relates naturally to its derivation from the figures above.

The complete blue line for Double Oxford Minor is shown on the right. The dots show the start points for each inside bell. It is shown in the conventional way running from top to bottom. This relates naturally to its derivation from the figures above.

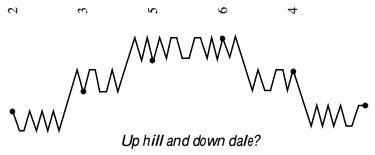

Some people, and a few publications, show blue lines running from left to right, as shown below.

This has the advantage that hunting ‘up ’ or ‘down ’ corresponds to upwards or downwards on the page.

Figure 15.2-1 - Types of hunting

Figure 15.2-1 - Types of huntingThe basic framework of most methods is plain hunting (or treble bob hunting for treble bob methods).

Figure 15.2-2 - Single dodges

Figure 15.2-2 - Single dodges Dodges appear in nearly all methods. Strictly, a dodge is a single backward step that interrupts hunting, but most people think of the dodge as a slightly larger unit that includes some of the hunting and/or place making on either side. The diagrams show both up and down dodges, and how the work of the two dodging bells fits together.

Figure 15.2-3 - Multiple dodging and places

Figure 15.2-3 - Multiple dodging and placesMultiple successive dodges form large units that are recognisable in their own right. Some methods substitute Kent places where a dodge might otherwise occur. This substitution only swaps two blows in two rows, but feels quite different to ring because of the place making, and because the two bells cross on the opposite stroke.

Figure 15.2-4 - Place making

Figure 15.2-4 - Place makingPlaces made are also often thought of not as single blows but as small pieces of work including the adjacent hunting. Places are sometimes made over or under another bell in a way that makes it easier to ring if this is understood. The examples show the common seconds made at a lead end in many methods and the way 3rds and 4ths are made at a single in methods such as Plain Bob.

Figure 15.2-5 - Court places:

Figure 15.2-5 - Court places:Court places are made next to the treble, and the line crosses the treble’s path. This over and under relationship occurs in many other situations, where a bell ‘runs through’ a pair of places, eg in Cambridge and Yorkshire places (see below).

Figure 15.2-6 - Work with interesting names

Figure 15.2-6 - Work with interesting namesSome sorts of work acquire names by visual association. There are many variations. Here are three common ones.

Figure 15.2-7 - Work found in Stedman

Figure 15.2-7 - Work found in Stedman Stedman is very different from most other common methods, but because of its popularity the forms of work within it have acquired names that are widely known. These names are sometimes used where similar work occurs in other methods.

Figure 15.2-8 - More complex sets of places

Figure 15.2-8 - More complex sets of placesSurprise methods give rise to many named pieces of work. Here are three of the more common (thick lines) with samples of the work that complements them (thin lines).

Several different schemes are used to record compositions . Some are more suited to shorter touches and some are better for long ones. Examples can be seen in The Ringing World Diary and other ringing publications.

Figure 15.3-1 - Listing the calls (or absence of them) for each lead

Figure 15.3-1 - Listing the calls (or absence of them) for each leadP,S or B indicates whether each lead is plain, has a bob or has a single. The grouping is a reminder of the repetitive structure of the calling.

Figure 15.3-2 - Writing out each lead head

Figure 15.3-2 - Writing out each lead head Each lead head is written out. Those with calls are marked, – (dash) for bob and S for single. (The final lead head is not rounds, since touches with an odd number of rows come round at hand stroke the preceding row. The lead head is then the first row after rounds.)

Figure 15.3-3 - Only writing those with a call

Figure 15.3-3 - Only writing those with a call Only those leads where there is a call are shown. The numbers on the right indicate how many leads there are between successive calls.

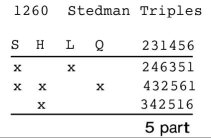

Figure 15.3-4 - Writing the number of the sixes in which calls are made.

Figure 15.3-4 - Writing the number of the sixes in which calls are made.Each number represents the number of a six at which there is a call. A bob is assumed unless the number is prefixed with an S.

Figure 15.3-5 - Setting out a grid of courses and calling positions

Figure 15.3-5 - Setting out a grid of courses and calling positionsEach line represents a course and each calling position used has a column. Calls are shown where they occur in each course. The lead heads are written out as before. Numbers are used for calls in positions where the lead repeats allowing multiple calls (B & I).

The second example is a twin-bob composition. Each (twin) calling position has a column.

The second example is a twin-bob composition. Each (twin) calling position has a column.

Some times 'five part' is abbreviated to 'x5'. Traditionally it would have said '4 times repeated'. While this is perfectly correct it is more confusing and most people have been tripped up by it at some time.

Figure 15.3-6 - As above but with the coursing orders

Figure 15.3-6 - As above but with the coursing ordersThe calls are set out as in the previous example, but instead of the course heads, coursing orders are shown in the right hand columns. There is a column for each calling position, but by convention, they are only shown where they change, ie where there is a call.

The relationship between the coursing orders and individual rows lends itself to a mechanistic procedure to enable someone to tap out the rows of a plain hunt. Learning the pattern below would be much easier for most people than remembering all the rows or transposing them mentally as they go along.

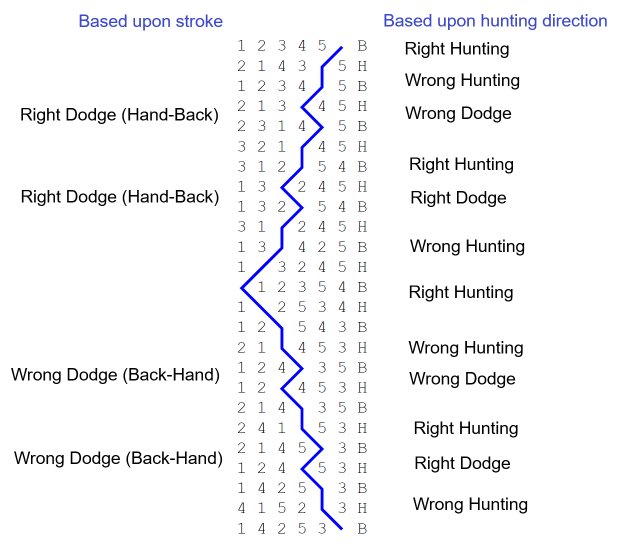

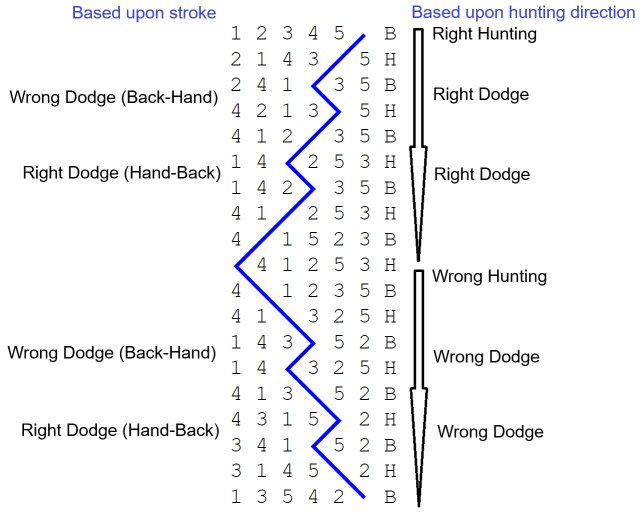

There are two different, conflicting, conventions for what dodging right or wrong means.

| Back to top | Return to Home page |