| Home page | Bellringing | Talks & lectures | Fell walking | Settle - Carlisle | Metal sculpture | Brickwork | Journeys | Ergonomics | The rest | Site map |

When the English art of ringing evolved over 400 years ago, bells were the principal means of mass communication and the churches in which they hung were used for many community activities, with only the chancel reserved for religious use. Bells were rung to make a loud and joyful noise on occasions of public rejoicing, and ringing as we know it grew out of this secular activity, as a sport and public entertainment. It was quite divorced from church services, for which a single bell was chimed. In the Puritan era, ringing (like many other sports and enjoyable activities) was considered sinful, and only survived because the public loved to hear ringing and the ringers were organised separately from the church. Ringers were paid to ring for public events.

Wokingham Churchwarden’s accounts show payment for ringing on nearly 50 occasions between 1808 and 1820, typically 10/- for six ringers, which in modern money would be a few pounds each. Most entries don’t specify the reason for ringing but in some cases it can be deduced, for example on 5 November to celebrate the foiling of the Gunpowder Plot, and in August 1818 for the ‘proclamation of peace’. Ringers often took their payment in beer – ringing could be thirsty work – which did not enamour them of the clergy in whose churches they rang.

In the 1830s the ‘Oxford Movement’ pushed the church back towards Catholicism and swept away many old practices. In the process there was a wave of ‘restoration’ of church buildings – removing box pews, musicians’ galleries, and triple-decker pulpits. No doubt the major changes to All Saints church in the 1860s were influenced by this.

The reforms didn’t touch ringers, who were still independent, but by the 1860s groups of ringing clergy were promoting ‘Belfry Reform’. Wokingham was at the heart of the process in this area. It was more or less central in Sonning Deanery, and from 1864 when St Paul’s church was built it had two ringing towers. On 23rd October 1879, the Chapter of the Rural Deanery of Sonning resolved: ‘That the Bell-ringers of the Deanery be incorporated in a Society for the encouragement of Change Ringing’ and that the following be appointed a Committee for carrying this resolution into effect:– Revds Dolben Paul, R. H. Hart-Davis, H. C. Sturges, J. F. Eastwood, and J. Fanklin Llewelyn, together with Mr. A. Hill, of All Saints Wokingham, and Mr. R. Blake of St. Paul’s Wokingham.

Most of those clergy were ringers, and the two laymen were both Wokingham ringers. Robert Blake, aged 46, was also Sexton at St Paul’s – an obvious establishment choice but Albert Hill was a young man of 24, a blacksmith by trade and a recent arrival in the town. He was born in Devizes and moved to Hampshire as a child before coming to Wokingham. He was a very able ringer and almost certainly learnt to ring before he came here.

Albert Hill in 1902 – He was Foreman at All Saints Wokingham from 1880 to 1896

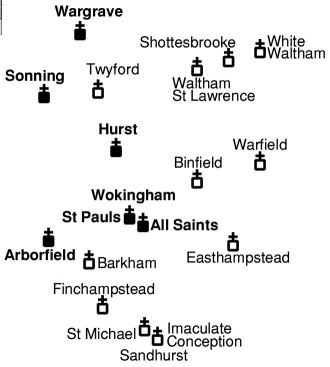

Six towers were founder members at the Society’s inaugural meeting – Arborfield, Hurst, Sonning, Wargrave and both Wokingham towers. They are shown black on the modern map of towers.

Towers in the modern Sonning Deanery Branch, with the six founding towers shown in Bold

The Society’s inaugural document said it was ‘formed for the encouragement of change ringing, and the cultivation of order, moral tone, and reverence in Belfries’. You might expect the clergy to encourage order, moral tone and reverence but why change ringing, which evolved as a secular activity outside the church’s influence and had no relationship to any liturgical music? The makes sense when you understand that ringing the bells in a fixed order, which was common in many places, is essentially a craft activity, using physical co-ordination skills akin to those used by working men, with a scythe in a corn field or a hammer in a smithy. But change ringing – continually changing the order of the bells in complex patterns – requires not only greater co-ordination to swing the bells at different speeds, but a significant intellectual input to memorise and interpret the complex rules for the changes. The reformist clergy were themselves ringers so they knew what they were talking about. They obviously thought that engaging the mind as well as the body would bring with it other more worthy mental habits and attitudes.

They were clearly satisfied with the result because sermons preached at several early AGMs referred to banishing ‘Churchyard Bob’ (ringing that wasn’t change ringing) and to ‘the higher tone among the ringers’. Belfry Reform left an enduring legacy. For change ringing, it stimulated more rapid and continual growth and advancement than during the previous couple of centuries. For ringers, almost all of them belong to one of the ringing societies formed by the reformers, which span the globe – whereas before there were just a few elite societies in centres of ringing. The Oxford Diocesan Guild, which grew out of the Sonning Deanery Society is now the largest in the world with around 2500 members. For the public, the reformers introduced the custom of ringing for church services, which now eclipses public ringing for other events.

John Harrison, September 2016

| Back to Top | Back to Articles | Back to What's New | Return to Home page |