| Home page | Bellringing | Talks & lectures | Fell walking | Settle - Carlisle | Metal sculpture | Brickwork | Journeys | Ergonomics | The rest | Site map |

All Saints is a mediaeval building with extensive Victorian modification. It is not a brick church. The external walls are stone, some of it rendered, and the internal walls are plastered (apart from the upper reaches in the tower). The building is notable for the extensive use of chalk as a structural material, especially the nave pillars – apart from two replaced because they were at risk of collapse, one in the 1860s and one in the 1950s – and the large gallery arch at the rear of the nave. There is some evidence to suggest that the church may originally have been built with chalk.

I have known the building for well over fifty years but it never featured in the ‘brick’ part of my life – until a recent major restoration project that included complete replacement of the floor with under-floor heating, and the creation of a new doorway through one wall. Figure 1 shows the nave at an early stage of the work.

Figure 1: View of the church floor after removal of wood blocks and tiles but before excavation

During the planning phase test pits were dug in the nave floor to check the foundations of the pillars. The floor had tiled aisles with wooden blocks under the pews, all laid on a concrete base in 1923, which in turn replaced a previous floor dating from major restoration in the 1860s. Beneath the concrete was a deep layer of rubble that included a lot of broken brick, and knowing of my interest in bricks the church historian invited me to see a test pit and to look through the couple of barrow loads of spoil that had been removed.

Most of the rubble was unremarkable but I found one fragment with part of an inscription. It was the corner of a brick with ‘20’ at the extreme end of the frog (Figure 2. left). The lettering that preceded it could have identified the maker but was missing. However I had a hunch that it might have been ‘TLB’ – a handmade brick by Thomas Lawrence of Bracknell, a dominant local brick maker who had many works in the area. But it was a rather tenuous hunch because I had never seen any TLB bricks with a number.

By chance a few months later someone disposing of a collection of old bricks contacted me, and among the bricks he gave me were two numbered TLB bricks (TLB 7 and TLB 29) that began to support my hunch. Both of these bricks had shaped ends, suggesting that the numbers might be shape codes. Later during the main excavation another numbered brick (TLB 17) emerged from the rubble under the church floor, but I couldn’t confirm whether or not it was a shaped brick because the end was missing (Fig.2 right).

Figure 2: Two fragments of Thomas Lawrence handmade TLB numbered bricks

During most of the project site access was strictly limited for safety reasons, which meant I could only inspect a very small fraction of the skip full per day that was extracted for several weeks. I got access to the floor once near the start and once at the end, and I was able to scan (the top of) a few of the skips of rubble. The site manager was friendly and offered to put aside any interesting bricks found, but unsurprisingly that produced very little with the workmen under pressure to get the job done and not knowing what to look for. It produced just two whole bricks – both copies of ones I had picked up when he first escorted me into the site. All the rest I found during my very limited access, but with a much keener eye.

As well as pieces of Thomas Lawrence handmade bricks (marked TLB) I found quite a few pieces of his machine made bricks (marked * WK * ) that were made in Wokingham about a mile from the church (Fig.3). These were all burnt and/or distorted, suggesting that they were rejects from manufacture, whereas the other pieces in the rubble looked normal (apart from being broken) so presumably came from demolition.

Figure 3: Different faces of three fragments of Thomas Lawrence machine made *WK* bricks

Another significant find in the rubble was a few bricks marked HGM (Fig.4). Henry George Matthews brickworks was in Bellingdon, Bucks about 50 miles from Wokingham. He began making bricks in 1923, the year the floor was laid. Interestingly the company is still in business a century later, and it still produces handmade bricks, some of which were used to repair the walls (see below).

Figure 4: Brick by Henry George Matthews (HGM)

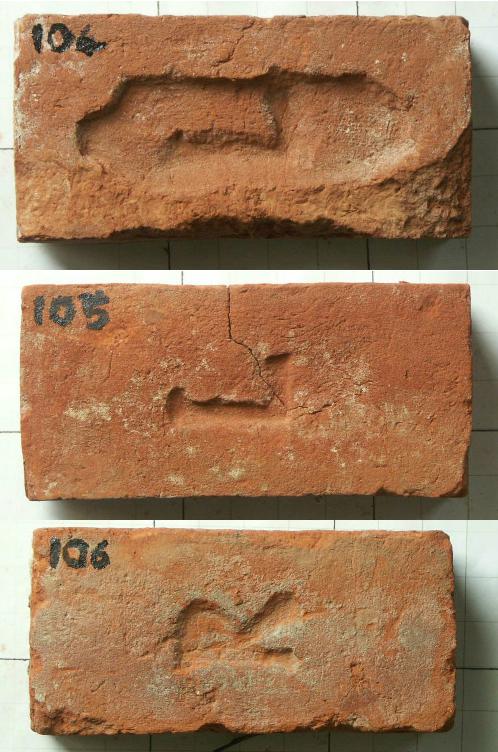

The previous floor included ducts (some of which are visible in Figure 1) that had large bore heating pipes covered by iron grills. The walls of the ducts were formed of brickwork – whole bricks that were presumably new when installed. Most of them were unmarked but a few had a large L or R on one face. Unusually the letters were aligned along the length of the brick rather than across it as normal – something I had not seen before. I found another brick with a sideways L but it was in a frog unlike the others which were on plain faces, and because it came from the skip I don’t know whether it came from the ducts or the under-floor rubble, but I assume the ducts since I didn’t see any whole bricks in the rubble. (Fig.5).

Figure 5: Three sideways lettered bricks from the pipe ducts

These whole bricks raise several so far unanswered questions:

When some stone memorials were removed from the north wall it uncovered brickwork, much to everyone’s surprise. And when the opening for the new door was cut through the wall, exposing the full cross section of the wall, it showed that the brick was far more extensive than just patches behind the memorials (Fig.6).

Figure 6: Right and left cross sections of the north wall

The wall was substantially rebuilt during the 1860s restoration by Henry Woodyer (1816 – 1896) and the outer layer is Bargate stone, which he also used for the new church of St Paul, a mile away, opened in 1864.

The inner layer of the wall is brick covered with plaster. Mostly the brickwork is single thickness but there is occasional deeper penetration into the wall,

The rubble fill in the middle of the wall includes sizeable pieces of both chalk and puddingstone (aka puddlestone). As mentioned above, chalk was used extensively in the original building, and puddingstone – a coarse, dark ironstone conglomerate – was used to build both the tower (around 1450) and the clerestory.

I examined a pile of about 200 of the bricks that came from the wall (probably 20% of those removed). None of them had inscriptions but some had frogs, and there were two different frog shapes (Fig.7).

Figure 7: Two different frogs of bricks from the north wall

The colour and texture also varied. Most of the bricks were a warm orange-red but some were a darker blue-red. This was most noticeable where bricks had broken to expose a clean, mortar-free internal surface (Fig.8).

Figure 8: Two different colours/textures of bricks from the north wall

The difference in colour and texture might be explained by manufacturing variability but the shaped frogs suggest there may have been more than one supplier. There were many brick makers in the area at the time. Michael Dumbleton1 mentions 17 brick makers that were operating in 1870 in a 9 by 7 mile area around Bracknell that includes Wokingham. The church wall was rebuilt a few years earlier than that so it seems there would have been plenty of choice.

[1] Brickmaking: A Local Industry, Michael Dumbleton, Bracknell & District historical Society, 1981.

[Article originally published in The British Brick Society Information 154, October 2023, pp 28-34 ]

John Harrison (October 2023)

| Back to top | Back to Articles | Back to What's New | Return to Home page |