You will find it useful to keep records for your own use. It can be difficult to keep track of just how long someone has been learning the same thing, or how many hours of tuition an individual has had, especially if lessons are at irregular times.

You will find it useful to keep records for your own use. It can be difficult to keep track of just how long someone has been learning the same thing, or how many hours of tuition an individual has had, especially if lessons are at irregular times.The Tower Handbook

You are all responsible, and in a real sense you all contribute to the teaching of your new ringers. One or two of you may act as Instructor [106] to run bell handling tuition, but that is only part of the story. Your trainees will learn from all of you. Whether they learn bad habits rather than good, whether they receive encouragement or not, whether they receive rich or sparse advice, whether they feel free to ask questions or not, will all depend on all of you, and on how willingly you share the responsibility for their development into fully fledged ringers.

Even in initial tuition, you can share some of the responsibility. If you are inexperienced at teaching, you can learn by assisting an experienced tutor. If you have experience of teaching, you could help share the teaching load, rather than let it all fall on a single pair of shoulders. See section 9.1h.

Breaking progress into small stages is a good teaching principle. As far as possible only teach one new thing at a time. This need not slow down the teaching process. Some stages may last only a couple of minutes. It may speed up the overall process because progress in later stages is not held back by things that were missed earlier on. At each stage tell the learner what you are about to teach and how you will both be able to judge the outcome. This means you must think in advance about the overall structure. It applies equally to the short period of time needed to teach basic bell handling and also to the much longer time needed to teach method ringing and full bell control.

There is no single best way to teach anything. Pupils learn in different ways, at varying rates, and respond differently. Flexibility is vital for good teaching.

Involve learners fully in the teaching process. Tell them what you will do and what you expect them to do. Give them a vision of the next few steps ahead, eg when they will progress to ringing on Sundays. Invite new recruits (and their families) to come along and meet the band before they start coming to the main practice. Encourage them to join in the band's social activities from an early stage. Let them see that the rest of the band enjoy ringing and that the band is a worthwhile group to belong to.

Yes, but try to tell them what they are doing right as well, and if possible more often. Learners do so many things less well than we would like. As teachers we are responsible for not letting them develop bad habits, but try to be positive. Say what to do rather than what not to do. Focus on things that are right, not just those that are wrong. Emphasise achievement. It works. People are motivated by feeling good about what they are doing, and the surge of feeling good helps to fix the right way of doing things in their minds.

Although generally it is a good principle to get one thing right before leaving it, there will be times when there are many faults, and you can't correct them all at once. Trying to do so would overwhelm your student. Decide what to tackle first, while saying there are other things to work on later. If other ringers are watching while you teach, they may spot things you have missed, but if you deliberately intend to delay tackling a problem, make sure they know you are concentrating on one thing at a time.

The biggest danger is after initial tuition, when your trainee starts to ring with others. There are many additional pressures, and bad habits can reappear. Be sympathetic about the increased mental and physical stress, but avoid slipping into the habit of not correcting faults at all at this stage. The longer you leave it, the harder you will find it to say anything and the more difficult your novice will find trying to break what by now will be a fairly solid habit.

No particular rate. People will progress at different speeds, not just from each other but at different stages. It is very common for a learner to appear to make little progress for a while, or even go backwards, and then make a great leap forward.

You will find it useful to keep records for your own use. It can be difficult to keep track of just how long someone has been learning the same thing, or how many hours of tuition an individual has had, especially if lessons are at irregular times.

You will find it useful to keep records for your own use. It can be difficult to keep track of just how long someone has been learning the same thing, or how many hours of tuition an individual has had, especially if lessons are at irregular times.

As an instructor you may find it helpful to compare the progress of different people. What was different, and did it have any effect? [107] You must allow for individual differences, but don't use that as an excuse for not trying to improve the other factors.

Neither - let them progress at their own pace. Don't compare them overtly with other ringers you are teaching now or have taught in the past.

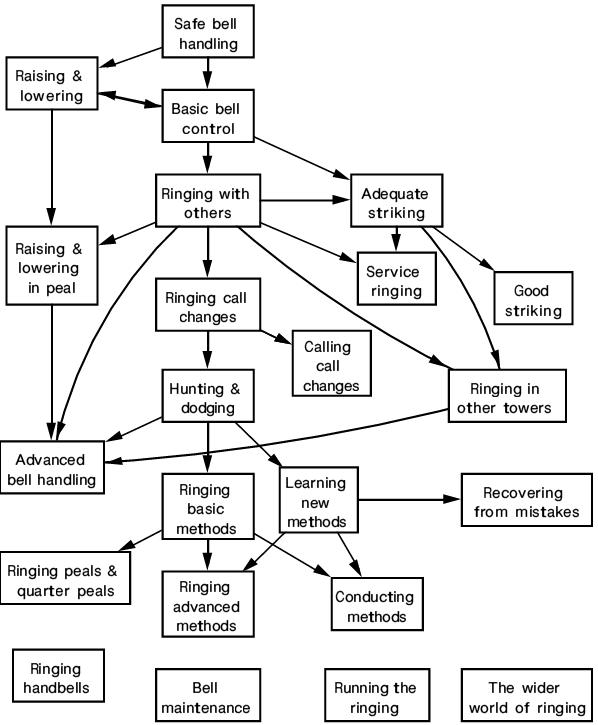

It is too restrictive to think of developing a new ringer as a serial process. If you do, you will miss opportunities. There are many strands to being a complete ringer, and you should aim to develop as many of them as possible. The richer and more diverse is the experience of your trainees, the more likely you are to retain them to repay your investment of time and effort.

Some components impose a natural order. Bell handling must precede ringing with others. Reasonable rounds must precede method ringing on tower bells. But overall there is scope for much variety and overlap, for example:

The diagram below gives some indication of the number of paths that your new (and not so new) ringers can follow. The arrows do not mean you have to progress that way, they merely indicate where one thing needs to precede another. Where there are no arrows there are no direct constraints on progression. For example, you could learn to ring handbells at any time.

Bell handling is a practical skill. Much of your teaching will be practical. But always explain the why and wherefore at each stage. People learn more quickly and perform better if they understand what they are doing, rather than just following instructions. Explain what ringing is about at the start. Make sure your pupil understands what is happening to the bell before (and during) teaching handling. Introduce the theory of call changes and method ringing before pitching into the practical side. Pencil and paper exercises are helpful and can occupy people when not ringing [108]. But don't let theory get too far ahead. Concentrate on general principles. Don't get bogged down in detail.

Good enough for what? It depends what you want the learner to do.

Each stage requires more skill than the one before. Remember also that more skill is needed on different bells, or when concentrating on something new. See section 11.3 on bell handling.

For the first few lessons the learner will probably be happier with the same teacher, and it is better for one person to be mainly responsible for an individual's progress. But there are benefits from exposure to more than one teacher and gaining different perspectives (but make sure they reinforce rather than contradict each other).

Give them exercises to do (theory, watching or listening). Keep relevant books and periodicals in the ringing room. Talk to them (quietly if during ringing) about things that interest them. Help them feel part of the group.

Currently hosted on jaharrison.me.uk