| Home page | Bellringing | Talks & lectures | Fell walking | Settle - Carlisle | Metal sculpture | Brickwork | Journeys | Ergonomics | The rest | Site map |

Part of my plan for publicity around VE Day 75 was to get an article on ringing and wartime into the history slot of our local newspaper for that week. It would follow on from the series that I had published a few years ago, and I could link it to coverage of local ringing for VE75.

I had a vague idea that the effect of the two wars was different, but I wanted some substantive evidence so I decided to do a bit of research. The newspaper covers a significant part of our Branch (Sonning Deanery, ODG) so I decided to focus my research on the Branch. That would make data gathering easier, and give a local focus to the article.

To set the scene I checked the dates and details of restrictions on ringing in each war. In WW1 ringing after dark was banned for about 2½ years (March 1916 – November 1919) with some easing towards the end, whereas in WW2 ringing at any time was banned for over 3 years (June 1940 – June 1943) apart from a couple of days.

Then I checked the number of ringers killed, which was easy thanks to the CC Rolls of Honour – I just searched for the names from each of our towers. Twenty local ringers were killed in WW1 – about one in seven of the pre-war Branch membership – whereas only one was killed in WW2. (A former ringer from my own tower, Wokingham All Saints, was also killed but he had already given up ringing a few years before the war.)

I was interested not just in what happened during the war but in the effect it had on what happened afterwards. One obvious measure to use is the number of members – how much did it decline during the war and how well did it recover afterwards? Another view is continuity of membership – how many members before were still ringing after, and how did the turnover differ from non-war periods? It seemed sensible to look at several years before and after each war rather than just a single year, and I thought four years should provide reasonably stable ‘before’ and ‘after’ conditions, but I found I needed to extend that.

My main information source was old Guild reports. Current reports list the ringers at each tower every year, but in some of the critical years, during and after the wars, the slimmed down reports didn’t do that. They all included accounts, so I tried using the subs paid by the Branch as a proxy for members. This was complicated by the fact that ‘Honorary members’ (non-ringing clergy and local gentry) paid a much larger subscription than ringers, and their numbers changed during the period. I then found information on who had paid subs in the Branch accounts book. A further complication is that during the period of interest some towers transferred into the Branch from adjacent parts of the Guild. I included the three towers that joined before WW1 (bringing the number from 9 to 12) but excluded the tower that joined just before WW2 (taking it from 12 to 13).

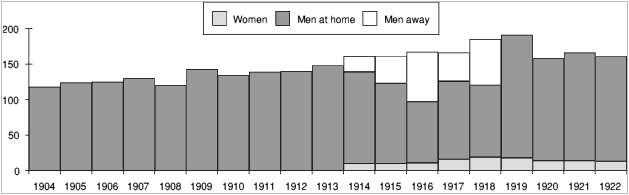

Figure 1: Branch membership before, during and after WW1 (adjusted for joining towers)

Figure 1 shows membership growing more or less steadily in the decade preceding the war, and during the war. It rose from around 130 in 1904 to around 190 in 1919. During the war ringing was certainly under pressure, with up to a third of the membership away on active service, but membership did not collapse despite the hardships. WW1 is well known as the spur for many women to enter the labour market to keep production and services going while men were away fighting, and many women also took up ringing. Women had undoubtedly rung much earlier in history, and the previous few decades had seen significant progress, notably the first all female peal and foundation of the Ladies Guild in 1912, but it is generally accepted that the war was a turning point for more widespread women ringers. In the Branch there were no women ringers before the war, but in 1915 there were 10, and that nearly doubled in 1918.

But despite the rapid growth, women in the Branch were a small minority, too few to offset the number of men away on active service (which peaked at 65 in 1918). In 1916 a third of the membership were away. The reason there were too few women is that only three towers had any women at all. In those towers women formed half the active membership (excluding men on active service) and 35% of the towers’ total members. But the remaining nine towers were apparently happy to ignore the potential of half the population.

After the war something odd happened. The membership that had grown steadily since long before the war, and had held up during the war despite restrictions, suddenly dropped. And it didn’t recover. For the whole of the inter-war period it remained 15–20% below the 1919 peak. The number of women ringers also dropped slightly, but nothing like enough to explain the overall drop.

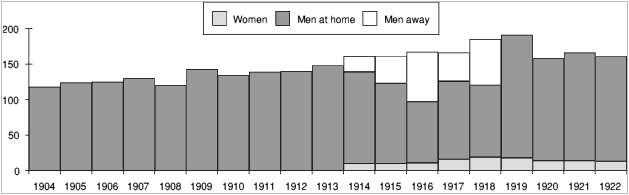

Figure 2: Branch membership before, during and after WW2 (adjusted for joining towers)

Figure 2 shows a very different picture from Figure 1. Membership during the decade before WW2 had fluctuated a bit but had not shown the steady growth that preceded WW1. In the first year of the war it fell over 10%, and when ringing was banned more than half the membership disappeared. Several towers recorded no members in the accounts books, but that might just mean the subs weren’t collected. Only a few towers had as many ringers as bells.

What about women ringers? With many women taking up ringing during WW1 one might have expected their number to continue growing during the inter-war years but it didn’t. In the run up to WW2 there were hardly as many women as there had been at the end of WW1, and they were still confined to very few towers.

When the ban on ringing was lifted in 1943 the membership grew again, and the growth accelerated after the war to pre-war membership levels. The number of women ringing also grew, and by the end of the 1940s they accounted for over 20% of the membership.

We’ve seen how the number of members changed through the war periods, but the membership isn’t a single entity – it is the aggregate result of many individuals taking up ringing, continuing to ring or giving up ringing. So membership numbers only tell half of the story. For example, steady membership numbers could indicate:

The underlying health associated with each of these scenarios is very different even if the numbers are the same. Scenario (a) may be good for now, but unable to recover from future losses from age or circumstance. Scenario (b) may seem harder work but should be better able to recover from any losses. Scenario (c) may come good but may not. It is like bailing a leaking boat instead of repairing the hole. Scenario (d) is missing the opportunity to expand when it could.

To look at turnover in the Branch I listed all members in sample years and compared the entries in different years to see how many were lost, how many gained and how many remained.

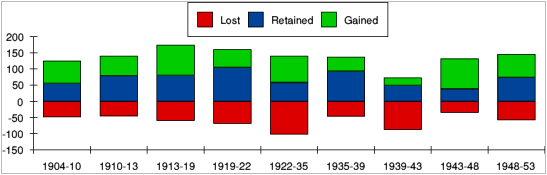

Figure 3: Membership changes during successive periods (NB not equal periods)

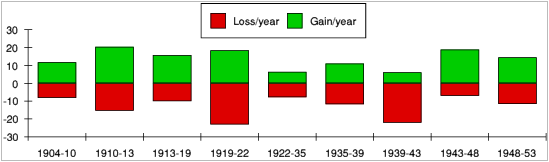

Figure 3 shows there were significant gains and losses in all periods, and also significant differences between the different periods. However since the periods are of different length (from 3 years to 13 years) it’s hard to make direct comparisons between them. To allow for that I produced Figure 4, which shows the average gains and losses per year during each period.

Figure 4: Gains and losses per year during successive periods

The differences in figure 4 are more apparent. Starting at the left, the annual turnover in the few years before WW1 was roughly double what it had been in the six preceding years. Turnover during the war itself was somewhat less than just before the war. In all three periods the gains exceed the losses, reflecting the steady growth in membership.

The bigger change was in the aftermath of the war, with large losses exceeding gains.

For the rest of the inter-war period turnover was quite low, but again it increased significantly in the run up to WW2 as it had before WW1. Was this coincidence, or a reflection of society responding to more uncertain times?

Losses in the first part of WW2 (before the ban was lifted) were as high as they were just after WW1, massively exceeding the gains. That situation was more or less exactly reversed in the five years after the ban was lifted, with large gains and relatively small losses.

Turnover was more modest by the end of the 1940s, but not quite as low as it had been during the inter-war years.

To get an idea of the relative scale of the turnover we need to see it in the context of the overall membership. Figure 5 does this by showing the average percentage of members retained each year.

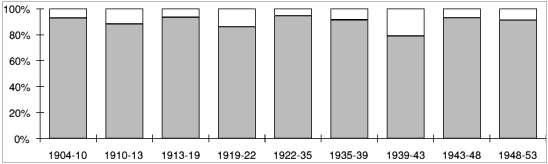

Figure 5: Percentage of members retained per year during each period

Nowhere was the annual retention more than 95%, and it was over 90% in all but three periods. In the run up to WW1 it was 88%, after WW1 it was 86%, and in the early part of WW2 it was 79%.

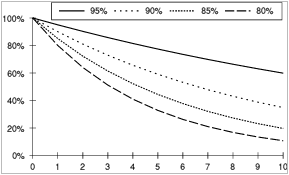

Retention over 90% might sound good, but it is compounded every year, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Cumulative effect of different annual retention rates

Even the best annual retention rate of 95% over ten years would reduce the membership to 60% without any recruitment, and a seemingly respectable 80% would take it down by a factor of ten in the same period.

The other readily available ringing statistic is the number of peals rung each year. It doesn’t represent ‘grass roots’ ringing but it is a measure of the activity of ringers who are likely to be proactive in an area, so it can provide some useful context. The number of peals rung in the Branch is too few to provide a reliable numerical indicator, and in any case a significant number of peals are not rung by local bands. So instead I looked at peals rung for the whole of the ODG, not just those in the Branch, and these are shown in Figure 7.

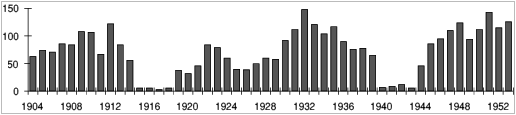

Figure 7: Peals rung for the ODG during all periods analysed

The number of Guild peals grew up to 1910 but fell again before the start of the war, in the same period where Branch membership turnover increased. There were very few peals during the war. Many men were away and there was a feeling it wasn’t appropriate.

Peal ringing recovered after the war but slumped in the late 1920s before peaking in 1932 and then declining again in the years before WW2. It would take more research to understand why this happened.

The wartime ban stopped tower bell peals, but in each year throughout the ban a dozen or so peals were rung in hand. As far as I can tell handbell peals had never been attributed to the Guild before that, and after normal ringing resumed very few were rung for several decades before Guild peals in hand became common.

The growth in peal ringing after lifting the wartime ban was more rapid and sustained than it had been after the previous war.

Both wars affected the production of Guild reports, which in normal times included a copy of Guild rules, lists of members by branch and tower, and details of peals rung for the Guild, as well as the officers’ reports and accounts.

During WW1 normal reports continued in 1914, 1915 and 1916 (produced in early 1917). In his 1914 report, the Master discussed how much the bells should be rung, discouraged peals and outings but encouraged service ringing, and emphasised the importance for Guild meetings (and associated ringing) to sustain ringers as a body. In his 1916 report, having spent almost the whole year abroad as an army chaplain, he commented on the Guild’s ‘good meetings’ and ‘steady educational work’. The message seems to have been ‘try to be as normal as possible’.

In 1917 the report was just a folded sheet with the accounts and messages from the Secretary and Master (still at the Front). The 1918 report (produced a couple of months after the war ended) was in the same format but with a few more pages to record ten peals that had been rung since 1916. In 1919 the report returned to its normal format and included several extra pages listing members who served in the forces, and In Memoriam of those who died.

During WW2 more reports were affected. The 1939 report (produced six months into the war) was the normal 70 or so pages) but the 1940 report (produced after the ban on ringing) was slimmed down by omitting the lists of members and just having the formal reports, accounts, and peals rung before the ban. This was undoubtedly in response to paper rationing, which the Master mentioned in a couple of his wartime reports. This minimal format persisted until 1946, though by then the number of peals had expanded it to 35 pages. Rationing of many things continued after the war and the reports seem to reflect this.

Despite the austere form of the documents, the officers’ reference to shortages, travelling restrictions and the blackout, their reports after 1943 contain a lot that was positive – increasing membership, training youngsters, restoring rings of bells and ringing more peals.

In 1947, some 2½ years after the war, the master reported: ‘It is a great source of satisfaction to all of us that we have this year succeeded in producing a report which is not only comparable in size to the pre-war editions, but also presents some new features.’

What does this research tell us about the effect of war on ringing, and about the differences between the effect of the two wars? And to what extent does the evidence support popular conceptions?

Let me start by listing some conceptions I had before doing this work:

How do these stand up (in Sonning Deanery Branch)?

Both wars seem to have had effects on the Branch that lasted after they were over. WW1 turned nearly two decades of growth into stasis over the following couple of decades, and the shock of WW2 led to a period of rapid growth and far greater presence of women. It would be interesting to know whether anyone has done similar research elsewhere.

John Harrison, April 2020

This article was published in The Ringing World on 1 May 2020.

| Back to top | Back to Articles | Back to What's New | Return to Home page |