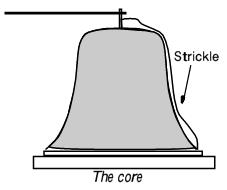

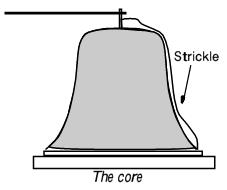

The core

The Cope

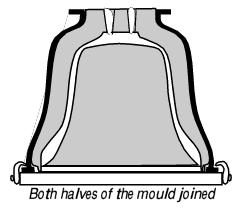

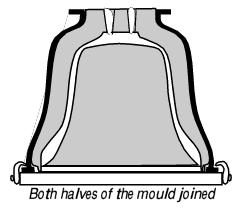

Both halves of the mould joined

The Tower Handbook

Church bells are cast in bell metal [38] (a form of bronze). The mould is made in two parts. The core or inner part is formed over a hollow brick core or shaped iron basket-like frame, while the cope or outer part is formed within an iron shell called a cask [39]. The surfaces of both inner and outer mould are made with a loam mixture, traditionally mixed with clay, horsehair and manure [40]. The shape is made with the help of a 'strickle' - a board cut to the cross section of the bell to be cast. Rotating it around the axis of the mould scrapes off any excess loam and shows up any depressions in the surface. The grooves for moulding wires are made by small protrusions on the edge of the strickle. The depressions for inscriptions and founders marks are made by pressing patterns [41] into the surface of the outer mould.

The two parts of the mould are fastened together to make a bell shaped space between them. The mould is dried slowly and heated to reduce the thermal shock when the molten metal is poured in. In the process, the organic material in the mould burns off leaving many fine channels that let the hot gasses escape when the bell is cast.

The core |

The Cope |

Both halves of the mould joined |

The gas then goes through holes in the cope and between the bricks in the core. The metal is melted [42] in a furnace and then moved in a crucible carried by a crane to the casting area where it is poured into the mould. After casting, sudden cooling could damage the bell, so it is left to cool slowly for several days before being removed from the mould and trimmed ready for tuning.

The full answer to this question would be long, technical and complicated, so we will break it down into a set of simple steps.

There is still room for variation in detail [44], and you can see this in the work of different founders, but if you have followed the steps of the argument you will see how the basic bell shape with which we are familiar has evolved to perform the function we require of it. If you change the function and add other constraints a different shape may be better. For example for a carillon or clock chime, hemispherical bells can produce a deeper tone in a smaller space than conventional bells of the same cost and weight.

Casting a bell to exactly the right shape would produce the right sound without any further tuning, but this is extremely difficult to do because the process of making the mould and casting the bell cannot guarantee the required accuracy. So the bell normally requires adjustment to make the different sound components blend together. Its overall note may also need altering to fit in with other bells in the ring.

If the sound when cast is close enough to what is required, it does not need tuning and is called a maiden bell. They are fairly rare, partly because founders play safe. It is easier to remove metal from a bell that is too thick rather than to melt it down if it is too thin. See the next answer.

Metal is carefully removed from different parts of the bell to lower or raise [45] the more significant frequencies (partials) generated when it is struck. Conventional modern tuning is sometimes called Simpson tuning after Canon Simpson who helped bring it into widespread use. In fact, he rediscovered the principles that had been used by Dutch bell founders some 300 years earlier. Five notes are tuned:

| Ideal ratio | Name | Comment |

| 1 | Fundamental | |

| 0.5 | Hum | an octave below (a major seventh [46] in some older bells) |

| 2 | Nominal | an octave above |

| 1.5 | Quint | (a fifth) |

| 1.2 | Tierce | (a minor third). |

The quint and tierce are in the octave between the fundamental and the nominal. Handbells have no sound bow and only two notes are tuned: the fundamental and a twelfth above that, ie three times the frequency.

A modern foundry uses a vertical lathe to remove metal accurately from the bell. In earlier times [47], the founder or bell hanger would use a cold chisel to chip off bits of metal. A modern bell tuner also has electronic analysis of the bell sound to assist him, whereas traditionally he would have used only tuning forks. In either case, he still needs a good ear.

A ring of bells rung full circle makes a glorious sound. Obviously the quality of the bells themselves is the starting point, but the same bells hung dead and chimed would not sound the same. Most chiming hammers do not hit the bell as hard as a clapper in full flight and this affects the tone produced. Chimed bells do not normally strike as rapidly as when they are rung full circle. Both of these factors could be overcome (stronger, heavier hammers and more rapid chiming) but the factor that is unique to full circle ringing is the Doppler effect.

When a sound source moves towards you its note rises and when it moves away its note falls. The faster the movement, the bigger the change. You will be familiar with this effect as trains or vehicles with sirens pass you. The speed of the soundbow of a bell is moving at several metres per second as it swings through the downwards position. This changes the note of the bell by a fraction of a semitone which is not a lot but is audible. This continual variation in all the bells as they swing adds an extra dimension that cannot be replicated with stationary bells.

The stay is like a hand brake on a car. It lets you 'park' the bell when it is up so you can leave it without having to stand and hold the rope between touches. The stay serves no purpose while you are ringing (apart from reminding you that you are not handling your bell properly if you bang it). Stays are only intended to be strong enough to hold the static weight of the bell when set. They are deliberately designed to break on heavy impact because the stay is a lot cheaper to replace than anything else that might break if the stay didn't. It is a bit like an electrical fuse which protects the rest of the wiring by being the weakest link in the chain.

No. Some very light bells have no stays. They would be harder to ring if they did, because people tend to swing the bells a long way over the balance and would keep banging the stays. Bells of under a hundredweight (50kg) can be raised to the balance by a single, really vigorous pull.

It is common practice in towers without stays to 'set' the bells by letting the ropes go right up (hand over hand) at handstroke after the ringing stops. The bells are then 180_ beyond the balance so they are mouth down, but with the ropes wound the long way round the wheel. The tail ends are at head height as if the bells were set at backstroke. When the next touch is about to begin, everyone pulls their rope down, hand over hand again, to bring the bells back to the up position ready to pull off.

Currently hosted on jaharrison.me.uk