The Tower Handbook

13.8: Learning to ring simple methods

a: What do I need to learn to ring simple methods?

To ring the method at all you need to learn:

- The work of the method (what happens when)

- Where you start

- How to make the bell do the work

To ring the method well you also need to learn:

- Ways of correcting your mistakes

- Ways of surviving other people's mistakes

Not only must you do all these things, but you must be good enough at doing them to have some concentration left over for your striking.

b: How many ways are there to remember a method?

Four basic methods with some variations (see below).

Many people use a combination, or remember different methods in different ways. You will not use them all at first, but we show them so you can see what is available that may help you later.

- Treble passing

A set of rules for what to do next, depending on where you pass the treble.

For Plain Bob Doubles, these are:

Pass treble in 1-2 == Make 2nds

Pass treble in 2-3 == Dodge 3-4 up

Pass treble in 3-4 == Four blows behind

Pass treble in 4-5 == Dodge 3-4 down

- Order of work

A string of instructions tell you what to do in sequence. You can include different amounts of detail. For example, Plain Bob Doubles could be:

(a) 'Lead, hunt to the back passing treble in 4-5, hunt down dodging in 3-4, lead, hunt to the back passing treble in 3-4, four blows behind, etc'

or

(b) 'Lead, pass treble in 4-5, 3-4 down, lead, pass treble in 3-4, four blows behind, etc'

or

(c) 'Lead, to the back, 3-4 down, lead, to the back, four blows behind, etc'

or

(d) '3-4 down, four blows behind, etc'

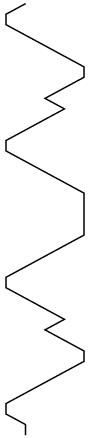

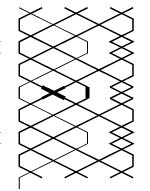

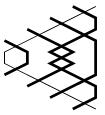

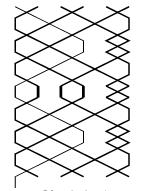

Blue line [176]

Blue line [176]

Instead of remembering words, you remember a picture, as shown right, also Plain Bob Doubles.

- Place notation

The location of any places made by any bells. This may not seem enough, but the places determine everything else that happens in the method. Place notation is normally used for complex methods. See section 13.10q.

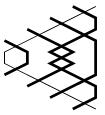

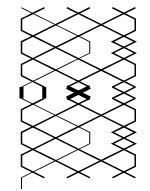

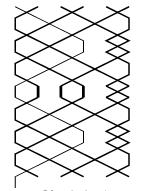

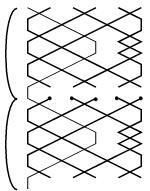

Structure

Structure

The way different blocks of work fit together. The structure of Plain Bob Doubles is simple. Under the treble all plain hunt, so there is no structure to remember. Above the treble everything happens when the treble leads. Two bells dodge together in the middle, sandwiched between those making seconds and long 5ths. This is shown in pictorial form in the diagram right, with the treble's path shown as a thin line.

c: Which is the best way of remembering methods?

No single way is best. They all have their strengths and weaknesses. You should be familiar with several approaches. You will find some are more helpful with certain types of method. To learn methods thoroughly, you need to combine more than one approach. Don't just confine yourself to the ways you have been taught. There are lots of little details and patterns you can spot in most methods, all of which will either help you to remember it, or help you to put yourself right quickly if you forget it. For example, with Plain Bob Doubles:

- People often use a mental image of the blue line to remind them of the order of the work if someone asks them what comes next.

- If you forget where you are in the order of work, you can put yourself right by spotting where you pass the treble.

- If you forget where you are on the blue line, and you know the structure, then you can put yourself right by seeing where the treble is and what the bells around you are doing.

d: Does it matter where you start?

The work is cyclic. Wherever you start, the end joins onto the beginning. Some books call it the 'circle of work'. You can learn a method starting anywhere, so long as you know all the places at which different bells start. This is true whether you learn it in words, or as a picture of the blue line.

A blue line is easiest to learn if you start from a point of symmetry. There are two such points in all normal methods, and one of them is always at a lead [177]. In 2nds place methods (like Plain Bob) this occurs where the 2nd starts. The other point of symmetry occurs at a half lead except when there is an even number of working bells (eg Plain Bob on even numbers or Grandsire on odd numbers). Many publications (eg The Ringing World Diary) print the blue line starting where the tenor starts. This is sometimes a point of symmetry, but not with 2nds place methods.

As well as learning the whole line, you must know where each bell starts. Learn the line as a set of 'place bells' (see section 13.10e) and you will.

e: Why is knowing where I pass the treble important?

In most methods the treble hunts (or treble bobs) and the structure controlling what the other bells do is built around the treble's path. As the treble moves from front to back (and back to front) it meets and passes every bell once [178], a different bell at each step. If you know that after passing the treble in so and so position you do a dodge in such and such place then it gives you an extra check on what you should be doing. And if you forget, it can help you find your way back. Passing the treble is a regular landmark worth learning.

f: How do I know which way round to dodge?

There are two ways to interpret this question. Many ringers have difficulty in knowing whether to dodge over at backstroke and under at hand, or vice versa. If you count your places carefully, there will be no problem.

There are two ways to interpret this question. Many ringers have difficulty in knowing whether to dodge over at backstroke and under at hand, or vice versa. If you count your places carefully, there will be no problem.

For example from the lead,

2nds place - handstroke

3rds place - backstroke

4ths place - handstroke

Now to dodge 3-4 your next blow steps back to

3rds place - backstroke

and you can then continue hunting up

4ths - handstroke

etc.

But life isn't so simple, and if you are worrying about what to do next, you can arrive where you know you have to dodge, but not sure to the nearest blow when the dodge will come. Lots of ringers do this, even those who ring fancy methods, but they know a very simple rule that puts them right.

- In most methods [179] where you dodge in even places (3-4, 5-6, etc) the blow in the direction you are going is at handstroke. This is true for up dodges and down dodges, so dodging in 3-4 up you strike over at handstroke, dodging in 7-8 down you strike under at handstroke, etc.

- In most methods where you dodge in odd places (4-5, 6-7, etc) the blow in the direction you are going is at backstroke. This is true for up dodges and down dodges, so dodging in 4-5 up you strike over at backstroke, and so on.

Since a dodge is really just a single reverse step in the middle of hunting, it would be more logical to remember the stroke at which you make this reverse step. Somehow thinking of the blow in the direction you are heading seems more positive, but do whichever you find easier.

g: How do I know which bells to make places over?

Make them over whoever is there! But it is helpful to know what is happening beneath you so you are not caught out. For example, in Plain Bob Doubles, when you make four blows in 5ths place, at a plain lead there is a pair of bells dodging under you. You have just passed one of them on the way up. If a bob is called, you still make the four blows, but the bells underneath do something different. One of them makes 4ths at the lead, ie under your second and third blows. Your last blow is over the bell that runs out, so you have now struck blows over all three other working bells.

If you like to know what is happening around you, rather than just taking it as it comes, write out parts of the method, with or without bobs, and work it out. Don't try to remember each bell (the combinations for all possible leads would be too much) but work out the pattern of what happens. For example, for a course of Plain Bob Doubles, look at which bells do what with which other bells at each lead. Then change the order of the bells at the start of the course (say start from 13425) and do it again. Can you see a pattern? You can do this sort of thing for any method.

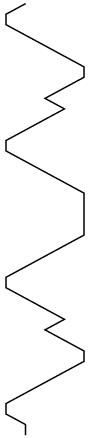

h: How do the pieces of work fit together?

They fit together because each bell can only move one place at a time and every place has to be occupied in every row. For example, if you dodge up, someone must dodge down with you. If you make a place, either someone must make a place under you, or two bells must change places under you. The same is true over you. The bells you pass just before or after making the place will be these same bells. Write out some of the methods you know and see if you can work out how the different pieces of work fit together. You may find it useful to draw out a lead and a half [180] of the method drawing the paths of all the bells on squared paper. Using different colours helps, especially for the treble.

i: What should I do if I don't know where I am?

You ought to know where you are, even if you don't know where you should be. We all forget what we are doing from time to time, but by the time you are ringing methods unsupervised, you should have developed the ropesight and awareness to know roughly where you are in the row. If someone tells you to dodge in 5-6, it won't help unless you know whether you are above or below 5-6 at the time. Similarly, if someone says 'dodge with me', you need to be aware where it is you are dodging, or you will immediately get lost again. People who don't know where they are tend to wreck touches because they don't respond to help.

j: How should I learn what to do at calls?

The work of a call in most methods only lasts for a single change [181]. Before and after that change you ring the method unmodified. If you learn what happens in this change, and how to join it into the rest of the method, you can make things much simpler.

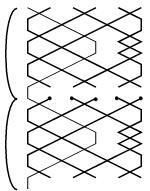

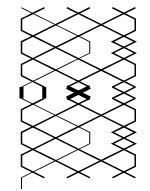

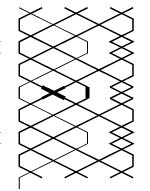

The left hand diagram below shows two leads of Little Bob Minor with the lead end change cut out. The treble's path is the thin line. The dots show the starts of each bell for the lead following the gap [182]. The second diagram shows the change for a plain lead put back in, and the third shows the change for a bob instead. The pieces that differ between the two are shown bold. It's not a lot is it! All you need to know is where you are at the beginning of the gap, what happens in the gap and your start after the gap. You can do the same for a single, shown in the right hand diagram.

Unaffected work |

Plain lead |

Bob lead |

Single lead |

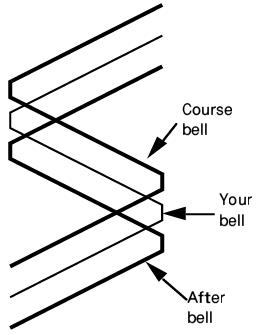

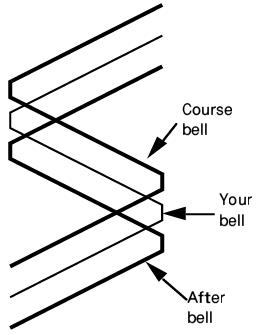

k: What are course and after bells?

Ringing a plain hunt, you follow your course bell around. Whatever you are doing, it is just ahead of you. You turn it from lead and from lie.

Ringing a plain hunt, you follow your course bell around. Whatever you are doing, it is just ahead of you. You turn it from lead and from lie.

Your after bell is exactly the opposite. It follows you around. You will see that you are your after bell's course bell.

In Plain Bob, things change a little. In some leads the treble appears where your course or after bell would be, (but if you have learnt where you pass the treble you should be able to make the adjustment).

It is worth remembering who your course bell is, so if you get in a mix-up, at least you have a landmark to aim for when you get to the back (or front). You can find your course bell as you go along, simply by noticing who you turn from behind. If there is a call it may change to a different bell, but you can soon pick up the new one. In more complex methods the order in which the bells move between leads is altered and so you may not come to the back between your course and after bell, though in many common methods you do.

Previous

Next

Next

Currently hosted on jaharrison.me.uk

Blue line [176]

Blue line [176] Structure

Structure  There are two ways to interpret this question. Many ringers have difficulty in knowing whether to dodge over at backstroke and under at hand, or vice versa. If you count your places carefully, there will be no problem.

There are two ways to interpret this question. Many ringers have difficulty in knowing whether to dodge over at backstroke and under at hand, or vice versa. If you count your places carefully, there will be no problem.

Ringing a plain hunt, you follow your course bell around. Whatever you are doing, it is just ahead of you. You turn it from lead and from lie.

Ringing a plain hunt, you follow your course bell around. Whatever you are doing, it is just ahead of you. You turn it from lead and from lie.