You have to learn to control four things properly:

You have to learn to control four things properly:The Tower Handbook

Ringing requires a unique blend of interlocking physical and mental co-ordination, but many of these skills are not unique. They are similar to the skills used by other activities. For example tennis, golf and cricket require accurately timed arm movements with visual co-ordination. Ballroom dancing requires bodily poise and movements synchronised to an external rhythm. Drumming requires arm strokes that start ahead of the beat and strike exactly in time.

You might not think of these analogies as you struggle with your first lessons in bell control, but there are many similarities. For example, when you first learnt to ride a bike, just staying on and steering without falling off seemed very difficult, let alone remembering to pedal. Ringing is the same. At first it is difficult to do everything at once, but eventually the 'mechanics' become largely automatic freeing our minds to concentrate on other aspects, like where we are going, and finding our way. If you can remember how long it took you to develop some of these earlier skills, it may give you comfort when the going seems slow with your ringing. It may also give a hint of the pleasure to be had when you perfect your skills.

Initially the choice will be made for you, probably a single bell. Most tutors will fairly soon give you the chance to ring other bells. Do not try to avoid this by sticking to the bell you know. It may be tempting, but you will learn more by ringing different bells.

If your tutor does not move you around, why not ask if you could try another bell? He or she will know which bells are suitable. When you have more choice over which bells you ring, aim to mix the ones on which you are confident and can ring well, with those you can manage but find a challenge.

Try to ring a variety of bells. They all behave slightly differently so you get the feel of a range of bell movement. See section 11.10d.

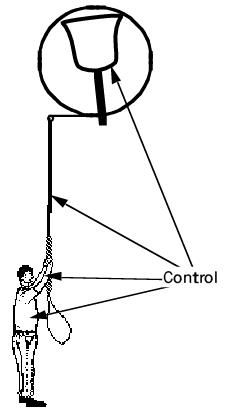

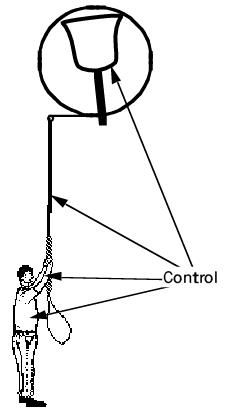

You have to learn to control four things properly:

You have to learn to control four things properly:

Each level of control relies on the preceding one, so to control the bell you must also control each of the others.

This is one of the most important questions in ringing. You must know when to do which, and train your arms to be able to do one without the other.

If you pull when you ought to check, or vice versa, you will make the problem worse. If you pull and check all the time, you will rapidly tire yourself but still not be able to control the bell very well.

Separating pulling from checking means you must be able to turn on or turn off the force in your arms between the rope rising and falling. This takes some practice, especially when you want to exert more effort. It is easier just to heave for the whole way up and down, but you must resist the temptation.

This is another important question. There are three things you need to do with the rope, and they affect how hard you should pull and when.

In summary, pull long and light as a baseline and modulate this with extra force as needed. Always use the minimum force to make the bell do just what you want.

If you pull too hard and/or ring with too short a rope, then it will tug at your hand at every stroke. If you then take in rope (because you are afraid it might pull out of your hand) it makes the problem worse. But if you were to lengthen your rope and not pull too hard, you would find the rope pulled less, so being nearer the end of your rope would not be a problem.

Controlling your rope length is vital. The length is the correct if your arms go to full stretch comfortably when the rope rises to the top of the stroke, at the speed you are ringing. Too short or too long and either you will stop the bell rising properly or your arms will not be taken to full stretch (giving you less feel and control).

Don't cling onto your rope with an iron grip trying to stop it slipping. If the rope length is wrong, it will eventually slip anyway, but you will make your hands ache. Relax your grip when you don't need to exert force on the rope. If you are relaxed you will be better able to feel what the bell is doing. Once you have developed the knack of making adjustments as you go along, you no longer need to worry about your hands slipping a bit. When you ring methods, especially on heavy bells, you will find you adjust the rope up or down quite often, but it becomes automatic.

Where you hold the sally at handstroke has the same sort of effect as where you hold the tail end at backstroke. In just the same way, it sometimes needs to be higher and sometimes lower. If you bring your hands up to the handstroke with the same rhythm as you take them up at backstroke, they will arrive on the sally at the right place, moving at the right speed. This is much more reliable than trying to spot a point on the sally and then grab it as it goes past. It is also self adjusting. Bringing your hands up more slowly is the equivalent of letting rope out, and vice versa.

Yes, in the same way that taking off and landing is part of flying an aeroplane. Sadly, in some towers people do not have the opportunity to become proficient at it. If bells had no stays, we would have no choice, but they do and it offers the temptation to miss out on developing this aspect of ringing.

Raising and lowering is a more demanding test of bell handling skills because things happen more rapidly, the speed and rhythm are changing, you do not have the comforting ability to hold up over the balance, and you have the added task of managing coils of rope. If you have not already done so, try to find a way to develop this part of your ringing skill. If you have done so, try to practice it regularly. See also Raising and Lowering in Peal.

Handling can be judged in two ways: by what is done and by the result.

A good style means:

A good style produces:

The things in the second list are what really matter, but they depend on other things as well as handling style.

Yes and no. In many places we emphasise that ringing relies on a sense of feel. But there is a danger. If you get into the habit of doing things badly, the wrong way feels natural to you. Worse still, if you try to change, the correct way may feel wrong because it is unfamiliar and so needs more effort. Many ringers have been allowed to develop a less than ideal handling style. Have you?

On familiar, easy bells, with undemanding ringing you may be able to cope. But do you ever find yourself in situations where your handling limits what you can achieve? Can you ring very light bells accurately? Can you ring bells as heavy as can other people of your build and fitness? Can you cope with long draughts or drawn ropes? Do you ever feel you are fighting the bell rather than having mastery over it? Handling style is not a fashion dictated by the ringing elite [156], it is a practical way to help you master your bell.

Good enough for what? Bell handling is not just something you do when you start ringing, it is the foundation on which all good ringing rests. You need to carry on developing, refining and broadening your bell handling skills long after you cease to have handling lessons. For a list of useful milestones, see section 11.3z.

Good enough for what? Bell handling is not just something you do when you start ringing, it is the foundation on which all good ringing rests. You need to carry on developing, refining and broadening your bell handling skills long after you cease to have handling lessons. For a list of useful milestones, see section 11.3z.

Bell handling is a means to an end, so the most important test is the result.

Does your handling prevent you striking well? Does it limit the bells you can ring? Is your rope always well behaved or a threat to anyone nearby?

You should be able to form your own view about these, but ask someone else who has watched you ringing in different circumstances. Pick someone experienced who you feel will give helpful advice.

A good teacher will tell you a lot, both initially while you are learning to handle the bell and subsequently as you progress to more advanced things. But your tutor will have other people to look after as well. He or she may have told you something once that you didn't hear or understand at the time, so may assume you know it. As we noted above, you should take some responsibility for your own development as soon as possible. Ask questions - you are likely to retain more than if you passively wait to be told. Read books on bell handling. Look at the questions and answers on teaching bell handling. See section 11.3. Observe other ringers, both good and bad.

Currently hosted on jaharrison.me.uk